Yesterday I told Diana that finding a summer job was going surprisingly slow, and the hunt was surprisingly difficult. I told her I thought this was God's little way of telling me I'd been riding my high horse when I started the job search and that I needed to be bucked right the hell off of it.

When I first started this summer job search, I said both to myself and out loud that it would be a piece of cake, that it would be no big shake, that I would be able to find waitressing work with no problem. Even if it came to it, I could probably go back to my old place of employment because they loved me there, they adored me, and they'd take me back in a hot second.

It turned out nothing was that easy.

In a fit of desperation a week or so ago, I turned into the driveway of a local sit-down pizza place because their sign had broadcast SERVERS NEEDED for the last month. It wasn't really the type of place I had in mind. It wasn't really the type of place I wanted to work for. But still I walked inside, asked to speak to someone about the needed servers, and was referred to the manager.

The manager made me wait five minutes just to speak with him. He took me into the closed-off section of the dining room, which is decorated with wood paneling and filmy watercolors circa 1972, and he started asking me questions. He wanted to know where I'd gone to school, what I'd studied, what kinds of jobs I'd held, what kind of waitressing experience I'd had.

When I listed the places I'd waitressed before, he nodded but seemed unimpressed. Then he sighed and shook his head.

"I don't know," he said. He sucked air in through his teeth, the universal signal for This is gonna be a close call. "See, I'd have no problem hiring you if you'd come to me maybe three months earlier. But you're not really worth it now."

I raised my eyebrows.

"Well," he said, "you see, it would take at least three or four months to get you trained in, and you only want to work for three months before you go back to your other job. I just don't see how that's worth it."

Three or four months? I looked at the man and thought, Surely you must be joking. This wasn't a four star restaurant. It was a quasi-Italian joint that served up plates of spaghetti to senior citizens and families with three screaming children who would've been thrown out of any other restaurant. When I was hired on at my last waitressing gig, we were all under the assumption that it was going to be a three month stint, and no one was worried about getting me trained in before those three months were up--and this was a restaurant that did banquets, had a full bar, and served things like Surf & Turf, not chicken bombers and french fry baskets. I wanted to tell this manager to give me an apron, show me the pop machine, introduce me to the cooks, and let me be on my way.

But instead I just smiled. "I understand," I said.

"You have pretty okay qualifications, though," he told me as some sort of peace offering. "How about I take down your name? I'll give you a call if I think we can work something out."

So I said sure and signed my name to a legal pad that was thick with the names of at least fifteen other women who must've come by and had similar experiences with this man. Just looking at those names--names like Ethel and Betty, and even names like Ashley and Lacey--I knew he'd turned away his fair share of the two best subsets of waitresses out there: the grizzled old-time waitresses who remember fondly the days when they could take their smoke breaks inside the restaurant and the cutesy just-graduating-from-high-school numbers who wear their hair in peppy blond updos and decorate their name tags with hearts and daisies. What else, I wondered, could this man be looking for?

But he was already herding me out the door. "It was a real pleasure to meet you," he said, and shook my hand. "No, I mean that. A real pleasure."

But today I had a little more success. Today I went on a job interview and actually landed a job. The head waitress who hired me didn't seem concerned that she wouldn't have enough time to train me in or that I wouldn't be able to grasp the nuances of the business in three full months. She just seemed to care that I knew I couldn't wear open-toed shoes or have my hair in my face. I told her sure, I was used to it, I knew the routine. I'd done this for five years of my life, after all. I said I was ready to give it another go--a lie, but a necessary one.

As I was gathering my things--which, now, included employment paperwork to be filled out and returned next week when I come for my first shift--she took one last look at my application. "I was looking at this the other day when the owner was in the room," she told me, "and I said to him, 'I think this has to be wrong. This girl is way too qualified to work here.'"

She laughed, so I laughed, even though I wanted to run back into the kitchen and jab myself with one of the biggest knives I could find.

"But, seriously," the head waitress continued, "I'm assuming this is just a summer thing, right? You'll be wanting to go back to school in the fall?"

I think she thought when I listed the university at which I work she must have confused that and thought I was going on to get a PhD because it was already listed quite plainly in front of her that I had both my BA and MFA. "Well," I said, "I'm not a student."

"You're not?" she asked.

"No. Actually, I teach at the university."

That's when she fanned herself with my application, like she'd been hit with a tidal wave of oppressive heat. "Oh," she said. "Oh. Well. You're definitely too qualified for this job. But I'm looking forward to working with you."

And my heart broke a little bit right then and there, standing in that cramped and disorganized office. I was feeling awful and nauseous and like I needed to have myself a good cry on the way home, but I was also feeling repulsed for feeling that way. What a brat, I thought as I drove the winding roads home, thinking about all the times over the summer I would drive that route, stinking of fish and grease. What a snobby, snobby brat.

But this is what it is, and it's unlikely that it will change, so I'll take my lumps. After all, a girl as snobby as me probably deserves them.

Thursday, May 31, 2007

Wednesday, May 30, 2007

The Things We Believe

The other day the Wily Republican and I got to talking about harems. Really, we were discussing the perks of being royalty, and he seemed to think that having a harem was an excellent fringe benefit.

I told the WR that when I was little I'd wanted to belong to a harem. Back then, I had these opulent, full-color cartoon books that retold all the best old tales, and one of the books was about Scheherazade. In that book there was page after page after page of willowy, tanned women draped in pink and purple and green veils, in tiny garlands of gold coins. I could imagine the way they sounded when they walked into a room, swishing, clinking. I wanted to be that kind of girl. I wanted to command attention when I breezed through archways. I wanted to lounge around on satin pillows and eat fruit and be amused by trained monkeys. It sounded like an okay life, but I didn't quite realize the implications of the harem. I didn't quite realize these ladies had a function other than being pretty and being audiences for monkeys.

The WR found this to be amusing. I'm sure the thought of me at seven years old, running around and draping hankies into my jeans so that I too could swish when I walked into a room, was pretty amusing. So he laughed.

"Yeah," I said. "It is funny what we'll talk ourselves into believing as children." Which reminded me of something else, something worse, something more moronic that I'd believed when I was young. But instead of being founded from something I'd read, this other belief sprung from something I'd watched.

I was eight years old when John Travolta and Kirstie Alley starred in Look Who's Talking. I was little. I was impressionable. I was stupid.

In the beginning of the movie, Kirstie Alley is locked in a passionate embrace with her boyfriend. They are about to have some sex on top of his big mahogany desk, but at eight years old, I didn't understand that was where this was going. I just saw the kissing, and that was something I did understand. When two people loved each other, they showed that love by kissing. Fine. But what happened next I did not understand. Not at all. The editing of the film shows the two kissing and then cuts directly to a shot of sperm racing toward an egg.

Oh my God, my eight year old brain thought. That's how a woman gets pregnant! By French kissing a boy!

Needless to say, that made me very nervous. People were always kissing on television, in movies, even out in the real world. I wasn't sure they knew what they were getting themselves into. After all, that sperm was pouring from the boys' mouths into the girls' mouths, and that meant that, in a matter of weeks, those girls could be sporting beach-ball size lumps under their tank tops. It seemed too dangerous to risk. So I made myself a promise right then and there. I would never, ever, ever, ever French kiss a boy unless I was certain I wanted to have babies with him.

I'm not exactly sure when I came around to thinking that this particular train of thought was inaccurate, but I do remember it took a long time. My mother tried to talk me out of it once, after I'd told her I had no interest in kissing a boy because I didn't want to make any babies. She tried to tell me that kissing didn't automatically mean baby, but I informed her that she didn't have to protect me. I told her I'd seen Look Who's Talking, and I knew what was up. My mother, I'm sure, had to walk out of the room then to go have a good laugh at my expense.

I would assume it took years of listening to snippets of conversation from the high school girls on the bus, listening to the boys in the lunchroom, and listening to things my friends had learned from older siblings for me to finally shake the belief that if I locked lips with a boy I might become a young mother, the kind that was always making tearful appearances on Oprah and Sally Jesse Raphael. And thank God for my coming out of that phase. Thank God. If I'd somehow continued on in my sheltered way, I would've missed so much goodness, and it took me long enough to get to that sweet point in my life as it was.

I told the WR that when I was little I'd wanted to belong to a harem. Back then, I had these opulent, full-color cartoon books that retold all the best old tales, and one of the books was about Scheherazade. In that book there was page after page after page of willowy, tanned women draped in pink and purple and green veils, in tiny garlands of gold coins. I could imagine the way they sounded when they walked into a room, swishing, clinking. I wanted to be that kind of girl. I wanted to command attention when I breezed through archways. I wanted to lounge around on satin pillows and eat fruit and be amused by trained monkeys. It sounded like an okay life, but I didn't quite realize the implications of the harem. I didn't quite realize these ladies had a function other than being pretty and being audiences for monkeys.

The WR found this to be amusing. I'm sure the thought of me at seven years old, running around and draping hankies into my jeans so that I too could swish when I walked into a room, was pretty amusing. So he laughed.

"Yeah," I said. "It is funny what we'll talk ourselves into believing as children." Which reminded me of something else, something worse, something more moronic that I'd believed when I was young. But instead of being founded from something I'd read, this other belief sprung from something I'd watched.

I was eight years old when John Travolta and Kirstie Alley starred in Look Who's Talking. I was little. I was impressionable. I was stupid.

In the beginning of the movie, Kirstie Alley is locked in a passionate embrace with her boyfriend. They are about to have some sex on top of his big mahogany desk, but at eight years old, I didn't understand that was where this was going. I just saw the kissing, and that was something I did understand. When two people loved each other, they showed that love by kissing. Fine. But what happened next I did not understand. Not at all. The editing of the film shows the two kissing and then cuts directly to a shot of sperm racing toward an egg.

Oh my God, my eight year old brain thought. That's how a woman gets pregnant! By French kissing a boy!

Needless to say, that made me very nervous. People were always kissing on television, in movies, even out in the real world. I wasn't sure they knew what they were getting themselves into. After all, that sperm was pouring from the boys' mouths into the girls' mouths, and that meant that, in a matter of weeks, those girls could be sporting beach-ball size lumps under their tank tops. It seemed too dangerous to risk. So I made myself a promise right then and there. I would never, ever, ever, ever French kiss a boy unless I was certain I wanted to have babies with him.

I'm not exactly sure when I came around to thinking that this particular train of thought was inaccurate, but I do remember it took a long time. My mother tried to talk me out of it once, after I'd told her I had no interest in kissing a boy because I didn't want to make any babies. She tried to tell me that kissing didn't automatically mean baby, but I informed her that she didn't have to protect me. I told her I'd seen Look Who's Talking, and I knew what was up. My mother, I'm sure, had to walk out of the room then to go have a good laugh at my expense.

I would assume it took years of listening to snippets of conversation from the high school girls on the bus, listening to the boys in the lunchroom, and listening to things my friends had learned from older siblings for me to finally shake the belief that if I locked lips with a boy I might become a young mother, the kind that was always making tearful appearances on Oprah and Sally Jesse Raphael. And thank God for my coming out of that phase. Thank God. If I'd somehow continued on in my sheltered way, I would've missed so much goodness, and it took me long enough to get to that sweet point in my life as it was.

Tuesday, May 29, 2007

The View from Our Place

Friday, May 25, 2007

If He Ever Says the Phrase "Pee Pee Head" to Me Again, I'm Going to Cut off My Ears

This is the first thing out of my father's mouth when he walks through the door tonight: "What are you going to do with those? They're too big."

He's talking about the cake I'm making for Becky's bachelorette party tomorrow night. In less than twenty-four hours there's going to be a group of girls in Ontario, Canada who are going to a bunch of strip clubs and drinking a bunch of duty free alcohol and eating a bunch of penis cake. Penis cake that I lovingly made. Penis cake that, unlike the one that showed up at my twenty-fourth birthday, doesn't have the herps.

When my father leans over to examine the raw materials of the to-be cake--two eight inch rounds and a 13x9 sheet cake--he looks concerned. "You'll need to make those smaller," he says.

I already know this. But it's disconcerting to hear my father comment on the testicle size of a bachelorette penis cake. Mainly because I don't ever want to discuss penises--fake or otherwise--with my father. It's enough that I've had to listen to twenty minute discussions between he and my brother about the agony of getting the down-there business caught in a zipper.

But even though it's wrong and dirty and gross, I call my father into the room when it's time to shave down the outer edge of the rounds. "Help," I say. "Want to cut them for me?" I am nervous about taking too much, about chipping away at this cake's dignity.

My father hands me a cereal bowl. "Should be about right," he says, and it is. The fact that he knew this so easily is also disturbing.

The next time my father saunters into the kitchen--Deadliest Catch is on commercial--he looks at my progress and nods. I have the shaft cut out, the balls whittled down. There is, however, one important thing missing.

"Are you going to give your cake a pee pee head?" my father asks.

I am holding a knife when he says this. It's a miracle I don't chop my ears off right then and there. While I've never thought about it before, it's completely clear at this moment that the phrase pee pee head is a phrase a father should never say to a daughter.

"Dad!" I wail. "Gross!" But then I motion to the leftover cake scraps. "And you don't have to worry," I tell him. "I'm on it."

Twenty minutes later, after carving and positioning and frosting, I have the final product on the giant platter my father sawed for me. (Here's your penis platter, he'd said after bringing it in and setting it in the kitchen.) I call my father in, gesture to the finished product.

"That," he says, "is a magnificent dick cake."

Oh, and it is. It's a straight shooter, smooth, ample in both length and girth. It's a blank canvas just waiting for filthy sayings to be piped onto its shaft with decorating icing. That, however, will have to wait until we get to the hotel room and it doesn't need to be moved anymore. It's going to be glorious.

He's talking about the cake I'm making for Becky's bachelorette party tomorrow night. In less than twenty-four hours there's going to be a group of girls in Ontario, Canada who are going to a bunch of strip clubs and drinking a bunch of duty free alcohol and eating a bunch of penis cake. Penis cake that I lovingly made. Penis cake that, unlike the one that showed up at my twenty-fourth birthday, doesn't have the herps.

When my father leans over to examine the raw materials of the to-be cake--two eight inch rounds and a 13x9 sheet cake--he looks concerned. "You'll need to make those smaller," he says.

I already know this. But it's disconcerting to hear my father comment on the testicle size of a bachelorette penis cake. Mainly because I don't ever want to discuss penises--fake or otherwise--with my father. It's enough that I've had to listen to twenty minute discussions between he and my brother about the agony of getting the down-there business caught in a zipper.

But even though it's wrong and dirty and gross, I call my father into the room when it's time to shave down the outer edge of the rounds. "Help," I say. "Want to cut them for me?" I am nervous about taking too much, about chipping away at this cake's dignity.

My father hands me a cereal bowl. "Should be about right," he says, and it is. The fact that he knew this so easily is also disturbing.

The next time my father saunters into the kitchen--Deadliest Catch is on commercial--he looks at my progress and nods. I have the shaft cut out, the balls whittled down. There is, however, one important thing missing.

"Are you going to give your cake a pee pee head?" my father asks.

I am holding a knife when he says this. It's a miracle I don't chop my ears off right then and there. While I've never thought about it before, it's completely clear at this moment that the phrase pee pee head is a phrase a father should never say to a daughter.

"Dad!" I wail. "Gross!" But then I motion to the leftover cake scraps. "And you don't have to worry," I tell him. "I'm on it."

Twenty minutes later, after carving and positioning and frosting, I have the final product on the giant platter my father sawed for me. (Here's your penis platter, he'd said after bringing it in and setting it in the kitchen.) I call my father in, gesture to the finished product.

"That," he says, "is a magnificent dick cake."

Oh, and it is. It's a straight shooter, smooth, ample in both length and girth. It's a blank canvas just waiting for filthy sayings to be piped onto its shaft with decorating icing. That, however, will have to wait until we get to the hotel room and it doesn't need to be moved anymore. It's going to be glorious.

Wednesday, May 23, 2007

Now He Thinks I'm a Lesbian, Too: Incidents with My Brother

1. At My Cousin's Graduation Party

Adam: I just can't get used to Jess's hair.

Me: He hates it.

Everyone Else: What? Why?

Adam: I don't like the bangs, and it makes her look gay.

2. At My Cousin's Graduation Party, Take Two

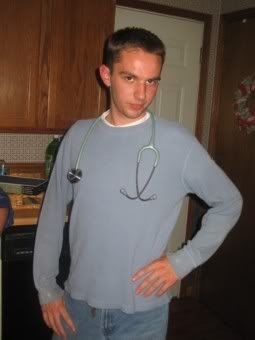

Me: Here, try on Kait's stethoscope.

Cousin Jeff: I got her that, you know. It's really nice. The last stethoscope she'll ever need. Well, unless she becomes a veterinarian.

Adam: Cool.

Me: Pose like a doctor, Adam.

Adam:

2. In My Car, 3:45 PM

Adam {out of nowhere}: You know what word is really funny?

Me: What?

Adam: Seminary.

Me: Really? Why?

Adam: It sounds dirty. Seminary. Seminary. Seminary. Semen-ary.

Me: Gross. Don't be foul.

Adam: Rectory's pretty good, too.

3. In My Car, 4:15 PM

Adam {out of nowhere}: You know what other word is really funny?

Me: What?

Adam: Masturbation. {He laughs--two quick and huffy ha! ha!s--then goes back to text messaging the girl he's going to a bonfire with later tonight}

Tuesday, May 22, 2007

What There Is to See

It was late that night, probably past two A.M. I was driving home from my boyfriend--Keith's--house, and I was driving the back way. I'd decided no, I didn't want to take the winding expressway home. Instead, I wanted to duck through the hills and valleys of what is, in winter, the capital of western New York ski country.

I had a soft spot for the back roads. After all, Keith was always driving me home that way. The road cuts through hills and pitches up and over their crests. There is one hill that is particularly troublesome--if you don't get a good run going up it, you swear you'll start sliding backward, swear your car will do an extravagant backflip like a clown car at a circus, like some Warner Brothers cartoon.

But that night on the way home I had a fine start up the hill. I made it up and over without a problem, and when I glanced behind me I could see the lights of the fading towns spinning and spinning into the darkness. I had to turn my eyes forward then because once I made it over the hill, I had to stop at a small looping crossroad.

And I did. I looked to my left to see if there was any traffic coming, but what I saw was not traffic. What I saw there, standing next to the stop sign was a pale young boy--eleven, maybe twelve--and he was looking at me. He was feet from me. He didn't move. He didn't seem startled. He didn't seem to want to hide from view, like he was trying to avoid being caught doing something troublesome out there at the stop sign in the middle of nowhere. I wanted to scream. But instead I slammed my foot on the gas and dove over the next hill to get away from that hill, that stop sign, that boy.

Mainly because I'm not entirely sure he was alive.

There was absolutely no reason for a boy that young to be standing next to a stop sign as casually as if he were waiting for a bus or a friend or a ride to school. Not at two A.M., not ever. The only reason to be out at that stop sign at two in the morning was to make mischief. But what was there to vandalize? Stretching out in front of him was nothing but night and fields. The only thing there was that stop sign, and what can you do to a stop sign when you're a twelve year old kid who can't even reach the words STOP? If you can't reach, then you can't attack the sign with a hammer, nor can you spray paint things like being a bitch, Mom! beneath the STOP.

I didn't look back. I couldn't look back. I didn't want my suspicions confirmed either way. I didn't want to see the kid still standing there, leaning up against that stop sign, and I didn't want to see the pale white moon of his face suddenly vanished into thin air. I just drove as fast as I could away from there.

For weeks, for months, I avoided those backroads at night just so I wouldn't have to confirm the reality of that moment. What did it mean if I drove that way again, and again there stood a boy in the moon-white light of two A.M.? Did it mean there was a serious sleepwalker in this tiny town? Did it mean there had been some accident years ago, right there on that corner, and every night the boy stood at the sign thinking about what could have been different, what should have been different?

I didn't want to know. I still don't want to know. But today I drove those hills again, looking for restaurants that might want to hire me as a waitress. Today I passed that stop sign twice--on the way to and on the way from that town, one of my favorites--and each time I stopped at that corner I looked to the left and studied the area very carefully. I was looking for tiny mementos: a wreath of dried flowers, a tangle of weathered ribbons, a teddy bear lanced to the telephone pole that stood nearby. I was looking for things a mother or a father or a sister would leave in memory of someone who was lost, a little boy, a son, a brother. I was looking for things that said, I miss you, I love you, come home.

I didn't find anything, though. But I couldn't stop thinking about that night and what it might be like if I got a job at a restaurant over that hill. What kinds of things would I see late at night as I drove home through the countryside with my apron pooled on the seat next to me, with the car windows rolled all the way down? Would I see that little boy again? Would he still be there, looking out across the hills and the winking lights wondering how he would ever get to where he needed to go, or would I be the only one stopped at that sign and wondering the same exact thing?

I had a soft spot for the back roads. After all, Keith was always driving me home that way. The road cuts through hills and pitches up and over their crests. There is one hill that is particularly troublesome--if you don't get a good run going up it, you swear you'll start sliding backward, swear your car will do an extravagant backflip like a clown car at a circus, like some Warner Brothers cartoon.

But that night on the way home I had a fine start up the hill. I made it up and over without a problem, and when I glanced behind me I could see the lights of the fading towns spinning and spinning into the darkness. I had to turn my eyes forward then because once I made it over the hill, I had to stop at a small looping crossroad.

And I did. I looked to my left to see if there was any traffic coming, but what I saw was not traffic. What I saw there, standing next to the stop sign was a pale young boy--eleven, maybe twelve--and he was looking at me. He was feet from me. He didn't move. He didn't seem startled. He didn't seem to want to hide from view, like he was trying to avoid being caught doing something troublesome out there at the stop sign in the middle of nowhere. I wanted to scream. But instead I slammed my foot on the gas and dove over the next hill to get away from that hill, that stop sign, that boy.

Mainly because I'm not entirely sure he was alive.

There was absolutely no reason for a boy that young to be standing next to a stop sign as casually as if he were waiting for a bus or a friend or a ride to school. Not at two A.M., not ever. The only reason to be out at that stop sign at two in the morning was to make mischief. But what was there to vandalize? Stretching out in front of him was nothing but night and fields. The only thing there was that stop sign, and what can you do to a stop sign when you're a twelve year old kid who can't even reach the words STOP? If you can't reach, then you can't attack the sign with a hammer, nor can you spray paint things like being a bitch, Mom! beneath the STOP.

I didn't look back. I couldn't look back. I didn't want my suspicions confirmed either way. I didn't want to see the kid still standing there, leaning up against that stop sign, and I didn't want to see the pale white moon of his face suddenly vanished into thin air. I just drove as fast as I could away from there.

For weeks, for months, I avoided those backroads at night just so I wouldn't have to confirm the reality of that moment. What did it mean if I drove that way again, and again there stood a boy in the moon-white light of two A.M.? Did it mean there was a serious sleepwalker in this tiny town? Did it mean there had been some accident years ago, right there on that corner, and every night the boy stood at the sign thinking about what could have been different, what should have been different?

I didn't want to know. I still don't want to know. But today I drove those hills again, looking for restaurants that might want to hire me as a waitress. Today I passed that stop sign twice--on the way to and on the way from that town, one of my favorites--and each time I stopped at that corner I looked to the left and studied the area very carefully. I was looking for tiny mementos: a wreath of dried flowers, a tangle of weathered ribbons, a teddy bear lanced to the telephone pole that stood nearby. I was looking for things a mother or a father or a sister would leave in memory of someone who was lost, a little boy, a son, a brother. I was looking for things that said, I miss you, I love you, come home.

I didn't find anything, though. But I couldn't stop thinking about that night and what it might be like if I got a job at a restaurant over that hill. What kinds of things would I see late at night as I drove home through the countryside with my apron pooled on the seat next to me, with the car windows rolled all the way down? Would I see that little boy again? Would he still be there, looking out across the hills and the winking lights wondering how he would ever get to where he needed to go, or would I be the only one stopped at that sign and wondering the same exact thing?

Monday, May 21, 2007

These Legs, They Are Itching to Run

Last night when I went to bed my legs ached. They were heavy. They felt water-logged, thick, impossible to lift. They felt like they used to feel after I pulled a long Friday night waitressing shift, a shift where I delivered no less than seventy billion fish frys. They felt like they used to after I'd had to dash between kitchen and dining room after having conversations like this one:

Customer: You didn't bring me any tartar sauce.

Me: Yes, I did.

Customer: No, you didn't.

Me: The container is right there on your plate. You've already used some.

Customer: Oh, that? That's butter.

Me: No, that's tartar sauce.

Customer: Oh. Well, I need some more. I put that in my potatoes.

Yes, last night my legs felt like they used to feel after I'd come home from work having dealt with customers who couldn't tell the difference between butter--yellow in color, served in foiled pats--and tartar sauce--white with large green hunks of relish, served in a tub that sits on top of the fried fish, right next to a lemon wedge.

When I got into bed last night my legs felt like they'd run all day, like they wanted to keep running, like they wanted to pick me right up out of bed and send me down the hall, out into the night, down the cooling pavement, through the back roads of this small town until I came to something else, something different, something new.

There's a panic in me right now. This is partly because the semester is over and the summer is stretching out in front of me, blank and dangerous. This is partly because I had a really busy, really nice week last week. New Boy cruised into town and we showed him all that Buffalo has to offer (which, really, was The Anchor Bar and Niagara Falls), then Josh left for his summer job in Wisconsin. Before he left, we had a long day full of things like shooting a BB gun out his bedroom window and drinking shots of Southern Comfort at 2:30 in the afternoon. Now, though, it's quiet. And it will remain quiet until it's time for all the sinning we're going to do at Becky's Bachelorette party this weekend.

The quietness makes me feel guilty. It gives me time to think about things, things like I still haven't landed a full-time teaching gig, things like I probably could've done more to land a full-time teaching gig (I sent out another fifty applications? I should've sent out more! Seventy-five! One hundred!), things like I need to find a summer job, things like I think I'm a bad granddaughter, things like I want to get out of this town. There are crazy thoughts in my head right now. I want to get up and go. I want to pack my car and drive until I find some new college, some beautiful, ivy-covered college in New England, and convince the English department that it needs me, it needs me bad, and they just won't be able to live without me so they should just hire me now.

I think, though, I probably just need to breathe and wait. Breathe, breathe, breathe, and wait.

Customer: You didn't bring me any tartar sauce.

Me: Yes, I did.

Customer: No, you didn't.

Me: The container is right there on your plate. You've already used some.

Customer: Oh, that? That's butter.

Me: No, that's tartar sauce.

Customer: Oh. Well, I need some more. I put that in my potatoes.

Yes, last night my legs felt like they used to feel after I'd come home from work having dealt with customers who couldn't tell the difference between butter--yellow in color, served in foiled pats--and tartar sauce--white with large green hunks of relish, served in a tub that sits on top of the fried fish, right next to a lemon wedge.

When I got into bed last night my legs felt like they'd run all day, like they wanted to keep running, like they wanted to pick me right up out of bed and send me down the hall, out into the night, down the cooling pavement, through the back roads of this small town until I came to something else, something different, something new.

There's a panic in me right now. This is partly because the semester is over and the summer is stretching out in front of me, blank and dangerous. This is partly because I had a really busy, really nice week last week. New Boy cruised into town and we showed him all that Buffalo has to offer (which, really, was The Anchor Bar and Niagara Falls), then Josh left for his summer job in Wisconsin. Before he left, we had a long day full of things like shooting a BB gun out his bedroom window and drinking shots of Southern Comfort at 2:30 in the afternoon. Now, though, it's quiet. And it will remain quiet until it's time for all the sinning we're going to do at Becky's Bachelorette party this weekend.

The quietness makes me feel guilty. It gives me time to think about things, things like I still haven't landed a full-time teaching gig, things like I probably could've done more to land a full-time teaching gig (I sent out another fifty applications? I should've sent out more! Seventy-five! One hundred!), things like I need to find a summer job, things like I think I'm a bad granddaughter, things like I want to get out of this town. There are crazy thoughts in my head right now. I want to get up and go. I want to pack my car and drive until I find some new college, some beautiful, ivy-covered college in New England, and convince the English department that it needs me, it needs me bad, and they just won't be able to live without me so they should just hire me now.

I think, though, I probably just need to breathe and wait. Breathe, breathe, breathe, and wait.

Thursday, May 17, 2007

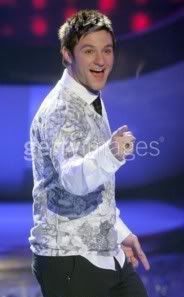

Notes on My Sometimes Unreasonable Love for Blake Lewis

Last night on American Idol when Ryan Seacrest threw to a commercial, he said, "And after the break, Melinda goes home."

"Notice how he said that," I informed my father, who was sacked out on the couch opposite me. Ryan Seacrest was supposed to be indicating that after the break we'd see film from Melinda's trip back to her hometown, where she would be greeted by legions of fans, where she would sign t-shirts, where she would get her name emblazoned on a road sign at her former school. But there was something sneaky in Seacrest's eyes. I narrowed my own at the television. I could tell something was up.

"Yeah, yeah, yeah," my father said. "I noticed that, too. But they would never do that. Never. They wouldn't dare."

"We'll see," I said. I could feel revolution in the air. It was just that type of night. Things in the universe were moving in strange circles.

I felt a little strange myself. I was torn in my thinking about who should go home. Melinda or Blake? Blake or Melinda?

It was a choice I took very seriously because I am a devoted American Idol fan, a girl who counts the days from one season's end to the next season's start, a girl who parks herself in front of the television every Tuesday and Wednesday night so she can say catty things about the people she dislikes (think: Sangina) and loving things about the people she worships (think: Chris Daughtry).

This year all my love has been Blake Lewis, Blake Lewis, Blake Lewis. I announced it during Hollywood week. He sang something particularly brilliant, something that made me stuff a hunk of chocolate into my mouth, and after it was done I sat back up and said, "That's my boy. I'm backing him. I'm voting him through to the end."

There was just something about Blake. I couldn't quite put my finger on it back then--mainly because I hadn't had enough exposure yet, hadn't had enough weeks to obsess over his performances, both good and bad--but I know what it is now.

I'm crazy about his stubble, crazy about the tone of his voice, crazy about his pronunciation, crazy about the way he holds his head when he sings.

When he sings, Blake tips his head back like he's trying to force his voice out from the pit of his stomach. It makes me want to kiss his throat. It makes me want to bite his stomach. It makes me want to curl up in his tonsils and listen to the wind of his voice rush up and over me.

When he sings, Blake doesn't necessarily finish his words. This is something our chorale director would've beat us for back in high school, but on Blake the quality is endearing. When he gets to the end of the word he sort of just lets it hang there, lets the sound fade off or melt into the next. It drives me crazy yet makes me want to gnaw on his jaw like it's a delicious pulled pork sandwich.

When he's not singing, Blake seems like a real stand-up guy. First, he loves his father. He calls him Daddy. And while I'm sure that's a quality that irritates every manly-man in America, I happen to think it's adorable. I'm completely willing to let this man be my father-in-law:

Also, it appears as though Blake gets along with everyone. For example, he and Chris Richardson were BFF as soon as they both landed on the show. Some hateful people might say this is just evidence that he is gayer than the day is long (and if that's true, fine. Instead of moving in with me so we can have sweet musically-inclined babies, Blake can move in and read He's Just Not That Into You out loud as I massage his shoulders and murmur That's so true, isn't it, Blake?--this scenario is equally as appealing) but I really like boys who aren't afraid to love their friends in an open way. For example, when Ex-Keith was drinking beer, he often liked to comment on his boundless affection for his best friend Greg by saying, Man, I love that tubby bitch. It was touching. I think Blake and Chris's relationship was touching in a similar way. And in a way that had me picking up the phone to call Amy and say, "You know, I think I'd pay a lot of money to see the two of them make out."

My love for Blake was cemented on Bon Jovi night when he did the beat-box version of "You Give Love a Bad Name." After that performance was over, my father shrugged and turned to me. "Well?" he asked. "What did you think of that?"

I tried to play it off all cool. "Oh," I said. "Well. Uhm. It was sort of weird, so I don't think the judges will like it." But what I really wanted to say was, WHY WON'T HE TAKE OFF HIS CLOTHES ALREADY?!

Of course, I can want Blake to take his clothes off for two reasons. The first is that he has done something well--sung brilliantly, did a cute little dance move, or beat-boxed with Sir Mix-a-Lot, for example--and the second is because the clothes the stylist has put him in are stupid. That tuxedo shirt on one of the results shows? Please. I thought we--as a nation, as a united front--were over the tuxedo t-shirt. Sometimes I have the distinct feeling that the show's stylist hates Blake. He often comes out onto stage in clothes that make him look a little thick, a little chunky. I also think they put eyeliner on him last week. And whose idea was it to dye his hair? If I were in charge of the show, I would tell that stylist to stop ruining Blake and keep concentrating on making Melinda look so much better than she did when she first came on the show, looking a little like a she-troll that had lived under a bridge for twenty years of her life.

But now, of course, Melinda is gone. And here's where I will say something shocking: I think that was a mistake. I think this week was Blake's week to go. Absolutely Melinda is a better singer. Absolutely she did a better job on Tuesday night. And if those are the merits we're supposed to be judging on, then Blake should've done his goodbye and gone back to Washington. Still, here's the thing: I think it's time for AI to launch a male pop sensation. The closest we've come is Clay Aiken, who we haven't heard from in a long, long time.

And I also think AI would ruin Melinda. I think they would make her do a record she wouldn't really want to do. The two people the show could do good by is Blake and Jordin. And Jordin, who is the better singer, should win. And probably will, unless Blake pulls out something miraculous and beautiful next Tuesday, which, if it happens, I will totally support. Almost as much as I support him making out with me or him making out with Jordin.

So I was happy last night when Seacrest and the producers pulled their trickiness and it was in fact Melinda who went home just as they'd hinted earlier in the show. I was happy that I called it and happy that Blake got to go over and stand next to Jordin and get transported into the final two, the final show, the Big Daddy of All Nights of TV. I'm excited to see what happens and how it all shakes out. And I'm interested to see just how many pieces of chocolate I will have to shove in my mouth to keep myself from announcing in front of my father that I want Blake Lewis to come live in my bed and wake me up in the morning by singing or--on weekends and big events--beat-boxing into my ear.

Oh, if only.

"Notice how he said that," I informed my father, who was sacked out on the couch opposite me. Ryan Seacrest was supposed to be indicating that after the break we'd see film from Melinda's trip back to her hometown, where she would be greeted by legions of fans, where she would sign t-shirts, where she would get her name emblazoned on a road sign at her former school. But there was something sneaky in Seacrest's eyes. I narrowed my own at the television. I could tell something was up.

"Yeah, yeah, yeah," my father said. "I noticed that, too. But they would never do that. Never. They wouldn't dare."

"We'll see," I said. I could feel revolution in the air. It was just that type of night. Things in the universe were moving in strange circles.

I felt a little strange myself. I was torn in my thinking about who should go home. Melinda or Blake? Blake or Melinda?

It was a choice I took very seriously because I am a devoted American Idol fan, a girl who counts the days from one season's end to the next season's start, a girl who parks herself in front of the television every Tuesday and Wednesday night so she can say catty things about the people she dislikes (think: Sangina) and loving things about the people she worships (think: Chris Daughtry).

This year all my love has been Blake Lewis, Blake Lewis, Blake Lewis. I announced it during Hollywood week. He sang something particularly brilliant, something that made me stuff a hunk of chocolate into my mouth, and after it was done I sat back up and said, "That's my boy. I'm backing him. I'm voting him through to the end."

There was just something about Blake. I couldn't quite put my finger on it back then--mainly because I hadn't had enough exposure yet, hadn't had enough weeks to obsess over his performances, both good and bad--but I know what it is now.

I'm crazy about his stubble, crazy about the tone of his voice, crazy about his pronunciation, crazy about the way he holds his head when he sings.

When he sings, Blake tips his head back like he's trying to force his voice out from the pit of his stomach. It makes me want to kiss his throat. It makes me want to bite his stomach. It makes me want to curl up in his tonsils and listen to the wind of his voice rush up and over me.

When he sings, Blake doesn't necessarily finish his words. This is something our chorale director would've beat us for back in high school, but on Blake the quality is endearing. When he gets to the end of the word he sort of just lets it hang there, lets the sound fade off or melt into the next. It drives me crazy yet makes me want to gnaw on his jaw like it's a delicious pulled pork sandwich.

When he's not singing, Blake seems like a real stand-up guy. First, he loves his father. He calls him Daddy. And while I'm sure that's a quality that irritates every manly-man in America, I happen to think it's adorable. I'm completely willing to let this man be my father-in-law:

Also, it appears as though Blake gets along with everyone. For example, he and Chris Richardson were BFF as soon as they both landed on the show. Some hateful people might say this is just evidence that he is gayer than the day is long (and if that's true, fine. Instead of moving in with me so we can have sweet musically-inclined babies, Blake can move in and read He's Just Not That Into You out loud as I massage his shoulders and murmur That's so true, isn't it, Blake?--this scenario is equally as appealing) but I really like boys who aren't afraid to love their friends in an open way. For example, when Ex-Keith was drinking beer, he often liked to comment on his boundless affection for his best friend Greg by saying, Man, I love that tubby bitch. It was touching. I think Blake and Chris's relationship was touching in a similar way. And in a way that had me picking up the phone to call Amy and say, "You know, I think I'd pay a lot of money to see the two of them make out."

My love for Blake was cemented on Bon Jovi night when he did the beat-box version of "You Give Love a Bad Name." After that performance was over, my father shrugged and turned to me. "Well?" he asked. "What did you think of that?"

I tried to play it off all cool. "Oh," I said. "Well. Uhm. It was sort of weird, so I don't think the judges will like it." But what I really wanted to say was, WHY WON'T HE TAKE OFF HIS CLOTHES ALREADY?!

Of course, I can want Blake to take his clothes off for two reasons. The first is that he has done something well--sung brilliantly, did a cute little dance move, or beat-boxed with Sir Mix-a-Lot, for example--and the second is because the clothes the stylist has put him in are stupid. That tuxedo shirt on one of the results shows? Please. I thought we--as a nation, as a united front--were over the tuxedo t-shirt. Sometimes I have the distinct feeling that the show's stylist hates Blake. He often comes out onto stage in clothes that make him look a little thick, a little chunky. I also think they put eyeliner on him last week. And whose idea was it to dye his hair? If I were in charge of the show, I would tell that stylist to stop ruining Blake and keep concentrating on making Melinda look so much better than she did when she first came on the show, looking a little like a she-troll that had lived under a bridge for twenty years of her life.

But now, of course, Melinda is gone. And here's where I will say something shocking: I think that was a mistake. I think this week was Blake's week to go. Absolutely Melinda is a better singer. Absolutely she did a better job on Tuesday night. And if those are the merits we're supposed to be judging on, then Blake should've done his goodbye and gone back to Washington. Still, here's the thing: I think it's time for AI to launch a male pop sensation. The closest we've come is Clay Aiken, who we haven't heard from in a long, long time.

And I also think AI would ruin Melinda. I think they would make her do a record she wouldn't really want to do. The two people the show could do good by is Blake and Jordin. And Jordin, who is the better singer, should win. And probably will, unless Blake pulls out something miraculous and beautiful next Tuesday, which, if it happens, I will totally support. Almost as much as I support him making out with me or him making out with Jordin.

So I was happy last night when Seacrest and the producers pulled their trickiness and it was in fact Melinda who went home just as they'd hinted earlier in the show. I was happy that I called it and happy that Blake got to go over and stand next to Jordin and get transported into the final two, the final show, the Big Daddy of All Nights of TV. I'm excited to see what happens and how it all shakes out. And I'm interested to see just how many pieces of chocolate I will have to shove in my mouth to keep myself from announcing in front of my father that I want Blake Lewis to come live in my bed and wake me up in the morning by singing or--on weekends and big events--beat-boxing into my ear.

Oh, if only.

Monday, May 14, 2007

On the Bus

We've been through this before. When I was younger, I was not what you'd call a beauty. In fact, I was not much of anything, save for the recipient of one too many Fantastic Sam's perms.

At twelve, I was logging long hours pining away for boys who played football on the town team, boys who dated cheerleaders, boys who French kissed before the age of sixteen, which is when I finally got down to business. At twelve, I was following Tammy around and watching as she--just by walking by--could cause a group of boys our age to snap their heads around as if they'd just witnessed some sort of minor miracle. And I suppose she was some sort of minor miracle. She was, after all, a twelve year old who didn't look angly, gawky, sweaty, nervous, or confused. Which were all the things I looked like as I trailed behind her, popping open Pepsi after Pepsi because I had a crush on the guy who sold them at the racetrack beverage stand and the only way I could get him to talk to me was to fork over a dollar at a time and then guzzle the pop on the way back to our seats.

In short, at twelve, I was a mess.

However, there was one place I wasn't a mess, a freak, or an ugly girl, and that place was the school bus. I was a different girl on that bus, mainly because it wasn't populated by people who could make fun of me. The high schoolers had a policy of ignoring everyone who wasn't above grade nine, and the elementary kids were too busy discussing what was in their lunchboxes to care about what went on in the middle of the bus, which was the middle schoolers' territory until the very last high schooler got off the bus. That's when we claimed the back as our own and practiced for the days that we'd get those seats by virtue of being the oldest, the wisest, the cleverest of the bus riders.

And while I was flying under the radar of the high schoolers and the elementary schoolers, I was being noticed for the first time by boys. These boys weren't the boys I wished would notice me--none of them were golden-haired Ryan McLean, after all--but they were boys nonetheless. And I wasn't stupid. I knew exactly how much power I had on a daily basis, and that amount hovered close to zilch for many years. But those bus boys got a little doughy in the face when I came around, so I learned to be thankful for the pinch of power I had during the forty minute ride to school and the forty minute ride home from school.

But after awhile--after love notes and declarations of feelings--I let it go to my head. I became a mean girl, an awful girl. I became a tease.

The boy I could tease the most was Justin.

His love for me was established early on, and this love lasted for years. He wrote me notes on the bus, in study hall, in social studies, in English, and at home. Later, when we were older and taking a language, he sat next to me in French and slipped me a note every single day. I would read it, write back, tap it up over his shoulder so it would fall gracefully on his desk without our teacher--an overweight man who was a man fond of smacking his pointer on the desk to scare students when they weren't paying attention--noticed what was going on. We had whole conversations this way.

You look good today, Justin would write. Are you ever going to let me kiss you?

Sure, I'd write back. In the back seat of the bus when Mr. Custard isn't looking.

I never let him kiss me in the back seat. But I did do something in the back seat, and what I did was cruel, cruel, cruel.

One day, teasing, Justin said I should wear my bathing suit to school so he could see what I looked like in it. I'd been bragging to him, telling him I'd gotten a brand new red plaid bikini and that I was going to show it off to all the Canadian boys over summer when I went up to Long Point. Justin said that wasn't fair. He said he wanted to see it. I told him the only way he'd see it was if he happened to show up at the local pool on a day when I was there. I told him that seemed very unlikely.

But I was lying. I was lying because I had a plan forming in my brain. I fully intended on having Justin see me in my new red plaid bikini because no other boy had any interest in seeing it, because no other boy was dreaming of seeing me in it, and because I needed to see what it felt like to be the center of attention, to do something scandalous, to do something that would send a boy's head spinning off its axis.

So I did. One day I substituted my bra for my bathing suit and carefully hid the halter straps under a thick t-shirt so my mother wouldn't see and wonder what on Earth I was up to. Our school didn't yet have a pool, so there was no reason for me to be donning the bikini under my school clothes. But I made it out the door without arousing suspicion, and I made it through the entire day without having a teacher or a friend grill me as to why there was a plaid bow tied under my hairline.

Once on the bus, I told Justin what was happening. I told him what I had in store for him. I said, "Just wait until you see this."

I could tell just by looking at his face that he was dealing with sensory overload. I think he was shocked, pleased, and terrified all at once. I think I was all three of those, too. This was a me that didn't show up at school. This was a confident me, a me that thought I was fun and interesting and impulsive. At school I was awkward and goofy and predictable. But for those eighty minutes each day, I had a chance to prove that wasn't all that there was to me.

I sure proved it the day I wore my red plaid bikini.

After most of the other kids had gotten off the bus, and after the middle schoolers had scuttled to claim the best seats in the back, I crammed myself into a corner and smiled at Justin, who was sitting in the seat across from me.

He wanted me to do it, do it, do it already. "Come on," he pleaded.

I did it. But right before I did, there was a moment--a terrible, sickening moment--that made me sit back and think, Is this really the best thing to be doing? I knew what I was doing to him, and I also knew what I was doing to myself. I was taunting him, and I was trying to grasp some measure of power by exploiting what little I had to offer in the attractiveness department. Justin loved me for things other than beauty. He liked that I was witty and willing to play with the boys. He liked that I had scathing things to say about other people on the bus and people we went to school with. He liked that I could spend the ride home writing stories that starred us as beloved crime-fighting heroes. I was different. Really different. And maybe that was just a little bit refreshing. But with this move, with this little red plaid bikini stunt, I would be trading in some of that. I would be saying, Now worship me for this. And what if that didn't work? What if it did?

Even though I knew there were a lot of better things for me to be doing with Justin right then and there--watching him load a straw with spitballs, for example--I peeled my shirt off and folded it in my lap. Then, triumphant, I leaned back against the window and rode the rest of the way home like that. Justin was happy with the result, and he talked about it for weeks. As for me, I was just starting to learn what a girl could do to mold a boy, to take him up in the palm of her hand, to turn him this way and that, to make him--even for forty minutes, for a bus ride, for a few short years--hers and hers alone.

At twelve, I was logging long hours pining away for boys who played football on the town team, boys who dated cheerleaders, boys who French kissed before the age of sixteen, which is when I finally got down to business. At twelve, I was following Tammy around and watching as she--just by walking by--could cause a group of boys our age to snap their heads around as if they'd just witnessed some sort of minor miracle. And I suppose she was some sort of minor miracle. She was, after all, a twelve year old who didn't look angly, gawky, sweaty, nervous, or confused. Which were all the things I looked like as I trailed behind her, popping open Pepsi after Pepsi because I had a crush on the guy who sold them at the racetrack beverage stand and the only way I could get him to talk to me was to fork over a dollar at a time and then guzzle the pop on the way back to our seats.

In short, at twelve, I was a mess.

However, there was one place I wasn't a mess, a freak, or an ugly girl, and that place was the school bus. I was a different girl on that bus, mainly because it wasn't populated by people who could make fun of me. The high schoolers had a policy of ignoring everyone who wasn't above grade nine, and the elementary kids were too busy discussing what was in their lunchboxes to care about what went on in the middle of the bus, which was the middle schoolers' territory until the very last high schooler got off the bus. That's when we claimed the back as our own and practiced for the days that we'd get those seats by virtue of being the oldest, the wisest, the cleverest of the bus riders.

And while I was flying under the radar of the high schoolers and the elementary schoolers, I was being noticed for the first time by boys. These boys weren't the boys I wished would notice me--none of them were golden-haired Ryan McLean, after all--but they were boys nonetheless. And I wasn't stupid. I knew exactly how much power I had on a daily basis, and that amount hovered close to zilch for many years. But those bus boys got a little doughy in the face when I came around, so I learned to be thankful for the pinch of power I had during the forty minute ride to school and the forty minute ride home from school.

But after awhile--after love notes and declarations of feelings--I let it go to my head. I became a mean girl, an awful girl. I became a tease.

The boy I could tease the most was Justin.

His love for me was established early on, and this love lasted for years. He wrote me notes on the bus, in study hall, in social studies, in English, and at home. Later, when we were older and taking a language, he sat next to me in French and slipped me a note every single day. I would read it, write back, tap it up over his shoulder so it would fall gracefully on his desk without our teacher--an overweight man who was a man fond of smacking his pointer on the desk to scare students when they weren't paying attention--noticed what was going on. We had whole conversations this way.

You look good today, Justin would write. Are you ever going to let me kiss you?

Sure, I'd write back. In the back seat of the bus when Mr. Custard isn't looking.

I never let him kiss me in the back seat. But I did do something in the back seat, and what I did was cruel, cruel, cruel.

One day, teasing, Justin said I should wear my bathing suit to school so he could see what I looked like in it. I'd been bragging to him, telling him I'd gotten a brand new red plaid bikini and that I was going to show it off to all the Canadian boys over summer when I went up to Long Point. Justin said that wasn't fair. He said he wanted to see it. I told him the only way he'd see it was if he happened to show up at the local pool on a day when I was there. I told him that seemed very unlikely.

But I was lying. I was lying because I had a plan forming in my brain. I fully intended on having Justin see me in my new red plaid bikini because no other boy had any interest in seeing it, because no other boy was dreaming of seeing me in it, and because I needed to see what it felt like to be the center of attention, to do something scandalous, to do something that would send a boy's head spinning off its axis.

So I did. One day I substituted my bra for my bathing suit and carefully hid the halter straps under a thick t-shirt so my mother wouldn't see and wonder what on Earth I was up to. Our school didn't yet have a pool, so there was no reason for me to be donning the bikini under my school clothes. But I made it out the door without arousing suspicion, and I made it through the entire day without having a teacher or a friend grill me as to why there was a plaid bow tied under my hairline.

Once on the bus, I told Justin what was happening. I told him what I had in store for him. I said, "Just wait until you see this."

I could tell just by looking at his face that he was dealing with sensory overload. I think he was shocked, pleased, and terrified all at once. I think I was all three of those, too. This was a me that didn't show up at school. This was a confident me, a me that thought I was fun and interesting and impulsive. At school I was awkward and goofy and predictable. But for those eighty minutes each day, I had a chance to prove that wasn't all that there was to me.

I sure proved it the day I wore my red plaid bikini.

After most of the other kids had gotten off the bus, and after the middle schoolers had scuttled to claim the best seats in the back, I crammed myself into a corner and smiled at Justin, who was sitting in the seat across from me.

He wanted me to do it, do it, do it already. "Come on," he pleaded.

I did it. But right before I did, there was a moment--a terrible, sickening moment--that made me sit back and think, Is this really the best thing to be doing? I knew what I was doing to him, and I also knew what I was doing to myself. I was taunting him, and I was trying to grasp some measure of power by exploiting what little I had to offer in the attractiveness department. Justin loved me for things other than beauty. He liked that I was witty and willing to play with the boys. He liked that I had scathing things to say about other people on the bus and people we went to school with. He liked that I could spend the ride home writing stories that starred us as beloved crime-fighting heroes. I was different. Really different. And maybe that was just a little bit refreshing. But with this move, with this little red plaid bikini stunt, I would be trading in some of that. I would be saying, Now worship me for this. And what if that didn't work? What if it did?

Even though I knew there were a lot of better things for me to be doing with Justin right then and there--watching him load a straw with spitballs, for example--I peeled my shirt off and folded it in my lap. Then, triumphant, I leaned back against the window and rode the rest of the way home like that. Justin was happy with the result, and he talked about it for weeks. As for me, I was just starting to learn what a girl could do to mold a boy, to take him up in the palm of her hand, to turn him this way and that, to make him--even for forty minutes, for a bus ride, for a few short years--hers and hers alone.

Friday, May 11, 2007

Long Live the Little Queens

When I was seventeen years old and a senior in high school, I announced I was going to enter a pageant. The Tulip Festival Queen's Pageant, to be exact. It was a part of the annual spring celebration that takes place in the town where I went to high school. Each year when the red and gold tulips yawn open along Main Street, a long train of carnival attractions roles into town. A midway is set up in the town parking lot, and it is dotted with funnel cake and taffy stands, with super slides and merry-go-rounds, with water pistol and dart games.

The Queen's Pageant is one of the biggest events of the three day extravaganza. It's like a mini-Miss America pageant for senior girls, just without the bathing suits. There's a dance routine, a talent competition, a gown competition, and a question and answer session.

And when I announced I wanted to enter the pageant, my parents and brother and Ex-Keith (then Boyfriend Keith) all looked at me like, Really?

I understood their looks. It wasn't my thing. I knew that. And even to this day I'm not exactly sure why I wanted to do it. I just know that one morning I woke up and said, "Well, I guess I'm going to do this."

I even surprised myself when I went to the informational meeting and came away still interested in going through with it. When I'd first stepped into that room, I figured there was a distinct possibility that I would leave thinking, Ha. Yeah right. But I didn't. Instead, I left thinking, Bring it on.

While it might take years of extensive therapy to suss out the real reasons behind why I did it, I can offer some possibilities. First, I wasn't fat anymore. Second, I had my first real boyfriend. Third, I was feeling better and sassier than I ever had before. Fourth, I was coming off a pretty bad heartache, and I think part of me wanted to strut around a stage, maybe get my picture in the paper. I figured the boy who broke my heart would see me in the paper and think about how good I looked, and then he would be filled with a sucking-gaping-awful-evil blackness because he'd done me wrong and hadn't made me his own.

But before I could grace the pages of the hometown paper, I had to face the competition. A handful of my friends were in the pageant with me, but so were a lot of the girls who'd sat court in the Very Popular zone back in middle school, back when people lived and died by those rankings. These were girls who'd had rumors spread about them in fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth grade--rumors that had them losing their virginities, getting pregnant, and being knocked around by their Very Popular boyfriends. In middle school, these girls were little queens, and I was the court jester.

A lot of that didn't matter anymore, but our histories were still there, still weighing heavily on our shoulders as we took to the stage the first time, as we stood in front of our dance coach, as we got the news that our opening number was going to be the most difficult opening number ever seen at the Queen's Pageant. We were going to be swing dancing. And that's when our histories bore down on us. Or maybe just me. I'd never had a single dance lesson. I'd never been that girl who spun circles in a pink tutu or, later, a leopard print leotard. But a lot of the girls standing next to me had. They'd danced at least some or all of their lives. I was screwed.

Everything else I had down. Dress? Check. It was floofy and my favorite color: purple. Talent? Check. I'd originally planned to read a fiction piece I'd been working on, but the powers that be thought it was too morose in subject matter (it was about the end of the world due to nuclear war) and it was nixed in favor of some poetry about Adam and Eve. Q & A? Check. I was like a little rockstar because I knew a lot of big words, and there's nothing that pageant judges like more than a girl who sounds like she knows what she's talking about.

Here's what I know about the dancing, though. I sucked. I sucked bad. I was always shrieking Sorry! to the dance instructor and the other girls when I messed up. Here's another thing I know about the dancing: I only ever did that routine perfectly twice, and, luckily, those two times were in front of the audience. After we'd done it for the last time ever, I remember feeling an immense amount of relief because I'd never, ever, ever, ever have to do it again. To this day, when our song comes on I still cringe a little inside.

But the pageant wasn't only about talent, pretty dresses, and smart-sounding responses. It was about community service, too. It was about being a mover-and-shaker. It was about being devoted to the western New York area. So, part of our obligation as Tulip Queen Candidates was to rove around the area, attending local Kiwanis meetings and mingling with the important men of small towns. We wore satiny little dresses and sat through plated meals of macaroni and cheese and casserole served up in the back room of local wing joints and restaurants. Part of the Kiwanis members' duty was to judge us. They were supposed to watch our table manners, assess our friendliness, and discern how poised we were.

We didn't go as a group, but we didn't go alone either. The powers that be split us up into pairs. Patty, who was still my best friend at this point, was my partner. We attended two dinners--both of ours were at smokey wing joints whose dining rooms smelled like old wood panneling and cheap beer--and at these dinners, Patty attempted to make me look bad. It was cutthroat, this competition. Patty was determined to come off more poised than I was, which wasn't really a hard task since I was just coming into my poise. But she was always finding ways to cut me down. When a grizzled old man I was seated next to asked what I was doing after graduation, I told him I was going off to college to be a English major. The man asked if that meant I wanted to be a teacher. Patty, sensing a way to capitalize on the conversation, leaned over and smiled at the grizzled man. "No," she said. "She doesn't want to be a teacher. There's not really one profession an English major prepares you for. I'm going into political science, though. I'm going to be a lawyer. I'll have a music minor, too. I sing and play flute."

This was some serious stuff. These dinners with the Kiwanis members, who would go scribble down their perceptions of us after the dessert course, were terrifying. After all, how did you make a good impression? How friendly was just-the-right-friendly? And how did you come off as poised? For me, I figured my poise shone through when I didn't kill my best friend, when I didn't stab her with a salad fork, when I didn't run us off the road and into a tree on the way home, even though I was very interested in impaling her on a tree branch.

But there wasn't much time to obsess about how well or not well those dinners went. The talent part of the competition was a major to-do for most girls. Me, I was easy. In the way of props, I asked for a fake tree and a bench. I sat on the bench under the fake tree and read my poetry. Other girls, though, didn't have it so easy. Some required fireworks--not real fireworks, of course, but things that were advanced for a high school production: music, projectors, sets.

One of the girls did a skit to "Paradise by the Dashboard Light." Another had a trellis and a projector for her interpretive dance to a Shania Twain song. Patty, always a fan of drama, had scripted a special note to be read before she went on. She wanted her performance--she was singing "Unforgettable"--to be dedicated to her just-born nephew, her middle sister's child. This sister--unwed and young--had slept with and been impregnated by a boy who then turned out to be gay, a boy who hightailed it out of state with his lover as soon as humanly possible.

Hers had been the most uncomfortable baby shower I'd ever been to. Patty's family was religious, and none of the situation really sat well with them. People were bone-white and dead-quiet at that party. Amy and I sat in a corner and tried not to say anything inappropriate, which was surprisingly difficult, given the situation. It was hard to accept that Patty's sister was just-graduated and pregnant. At the shower all I could think about was this one night the sister had come home from a date with the boy who would eventually get her pregnant. They'd been out walking, she said. It started raining. The air was thick and heavy with the smell of spring and blooming flowers. They were standing underneath the dripping branches of a lilac bush, and that's when he kissed her. It was the most amazing thing, she'd said. The most amazing feeling ever. At the time she told us that story, I hadn't been kissed. In fact, I was a long way off. But I felt something tug inside me. I knew what she meant. I could imagine the perfectness of that moment. I could imagine how everything smelled and tasted and felt like love.

But at her shower, I wasn't thinking about the loveliness of that anymore. I was thinking, Isn't it funny to go from there to here? But the drama wasn't about to end there for Patty's family. A few months later, both Patty's sisters would be hit by a drunk driver. Her pregnant sister went into labor and delivered that night.

And it was that fragile boy who was the feature of the slideshow that Patty had playing behind her as her voice skimmed over the notes of the old Nat King Cole song. A lot of people thought that was sweet, that was cute, that was precious. But I couldn't help think about the way Patty had looked when she sold me down the river over a plate of macaroni and cheese. I couldn't help but think about the cool smile on her face, the sly brush of her eyelashes against the hollows under her eyes, the way her voice came out as practiced as a weathered CNN anchor's. That was a girl who wanted to win, and she wanted it bad.

And it's not that I thought she was happy about what happened to her sisters and the baby, but I did think she was interested in the edge it could give her. There seemed to be a new confidence in her. It showed in the way she held herself, in the way she treated people. She knew she had a human interest story with bite. She knew she had a story that would look good in the paper, a story that would have audience members reaching for tissues as the photos rolled across the screen and she purred through the song's throaty notes.

But even as much as she thought her story was the golden ticket and her way to the crown, it wasn't. Just like my poetry about Adam and Eve wasn't my way to the crown. We both watched as one of the other girls--a girl who'd donned tap shoes and skittered across the stage the way she'd been doing since she'd been born--accepted the crown and took her victory walk clutching a dozen roses to her dress.

However, my vantage point was a little different than Patty's. I'd somehow managed to snag the third runner-up--a feat that had me crying as soon as the curtains snapped shut and all the girls gathered round to congratulate the court and the newly-crowned queen. I just couldn't help myself. I didn't realize until that moment how much I had riding on the results. I didn't realize how much it would mean to me to find a spot in the court, to actually get my picture in the paper, even if it showed me with puffy, tear-splotched cheeks.

While I stood on the tiered platform with the other runners-up I felt a little bit invincible, a little bit like this moment was trying to tell me there were better things to come, like I was going to find out that the things I wanted might come just a little bit easier now that I felt more capable to seek them out. And while I clutched my own roses to my dress and smiled into the flash of cameras, I thought about the night at the Kiwanis meeting, about Patty leaning over and informing the room that mine was a silly degree, a silly dream, a silly thing to want. While I stood there, I hoped whoever was taking pictures for the local paper was catching my smile the way it felt on my face right then. It was a smile whose angle and strength and earnestness was saying We'll see about that, won't we? We'll just see about that.

~~~

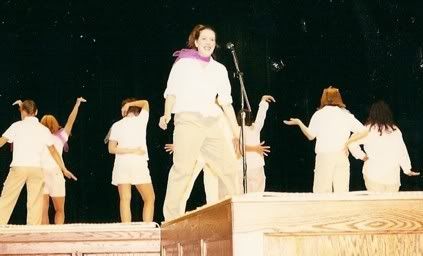

And, to celebrate that this weekend is, in fact, Tulip Festival weekend in the old hometown, here are some pictures of my pageant year:

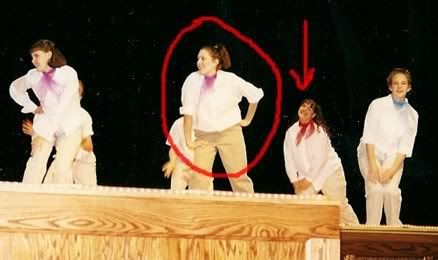

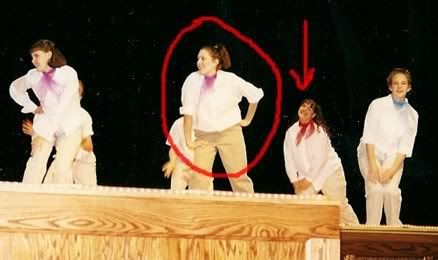

This the show opener. Each girl ran out on stage, chirped out her name (Hi, I'm Jess!!!!!) and then got in place for the swing dance.

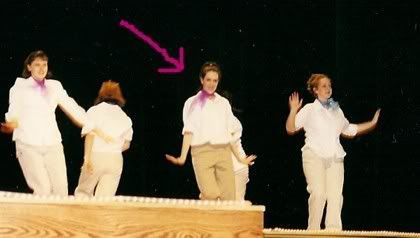

Here we are in the middle of the opening number. The circled girl is me, and, yes, I admit that I am wearing gross khakis and a too-big shirt. I thought it was cute at the time. I now recognize the error of my ways. The arrowed girl is Patty and Patty's This Smile Is Way Too Big to Be Sincere smile.

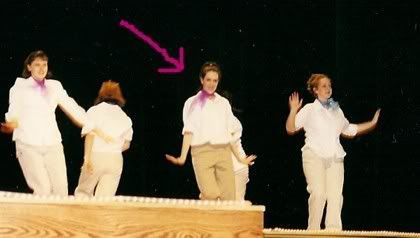

My jazz hands were working overtime.

Here's a washed-out picture of me doing a tour of the stage during the gown competition.

One of the perks of being a Tulip Queen contestant? Getting to ride around in a sporty borrowed car. The only problem with mine was the convertible top wouldn't go down, so I had to hang out the window to toss candy and wave.

Here I am accepting the flowers after being named to the court. If you look to the right, you can see Patty distracting Mary and Becky. It's possible she's saying something like, "Her? You've got to be kidding me!"

The Queen's Pageant is one of the biggest events of the three day extravaganza. It's like a mini-Miss America pageant for senior girls, just without the bathing suits. There's a dance routine, a talent competition, a gown competition, and a question and answer session.

And when I announced I wanted to enter the pageant, my parents and brother and Ex-Keith (then Boyfriend Keith) all looked at me like, Really?

I understood their looks. It wasn't my thing. I knew that. And even to this day I'm not exactly sure why I wanted to do it. I just know that one morning I woke up and said, "Well, I guess I'm going to do this."

I even surprised myself when I went to the informational meeting and came away still interested in going through with it. When I'd first stepped into that room, I figured there was a distinct possibility that I would leave thinking, Ha. Yeah right. But I didn't. Instead, I left thinking, Bring it on.